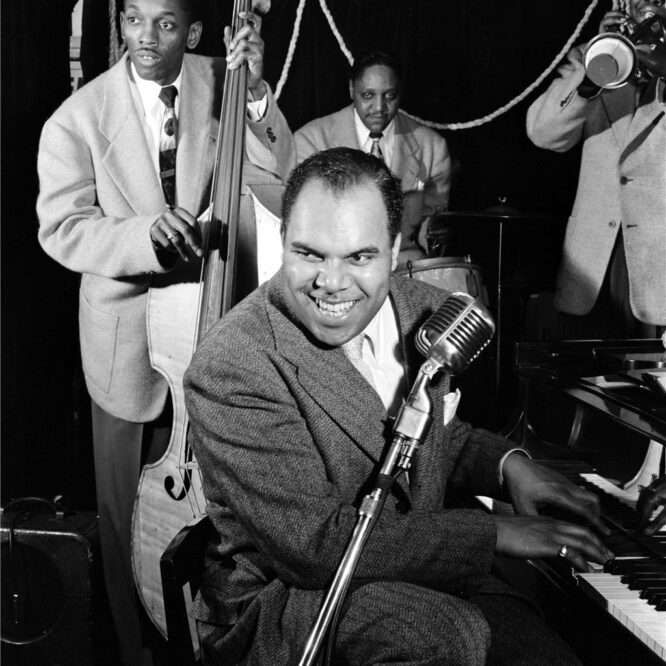

One of the most widely-recognized musicians in popular music and the winner of 28 Grammy Awards, Jones spent eight formative years in Seattle, where he learned to play trumpet, taught himself to arrange, toured with his first jazz band, wrote his first arrangements and befriended Ray Charles, who helped him with his early arranging. Born in Chicago, Jones came to Bremerton, Wash., with his family in 1943 and to Seattle in 1945, where Jones joined a swing band started by his classmate at Garfield High School, Charlie Taylor. Bumps Blackwell took over the band and got it gigs all over the Northwest, including a night backing up Billie Holiday. After graduating from Garfield in 1950, Jones attended Seattle University for a semester, then went to Boston, where he studied at the Schillinger school and was picked up as a trumpet player and arranger by Lionel Hampton. After forging a career as an arranger in New York, Jones drew upon three of his colleagues from Seattle – Floyd Standifer, trumpet; Buddy Catlett, bass; and Patti Bown, piano — for a big band that would be featured in a new musical in Europe, “Free and Easy.” The show bombed, but Jones stayed in Europe for 10 months, after which he became the first black executive at Mercury Records. Jones went on to write 30+ film scores, starting with the “The Pawnbroker,” in 1964, and including “The Color Purple.” He also produced Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” the best-selling pop album of all time. Jones continues to promote young jazz musicians through his record company, Qwest. … Continue readingQuincy Jones